This is my first blog and I want to share my learnings about containers

Container adoption to run enterprise applications softwares in production has been increasing drastically nowadays. And most of the container deployments are using docker. Docker became the defacto technology for running containerised applications. But what is docker built on? How it is containerising the applications? I will try to answer these questions in this article.

Need for the container

Before getting into containers, let’s clearly understand what a process is?

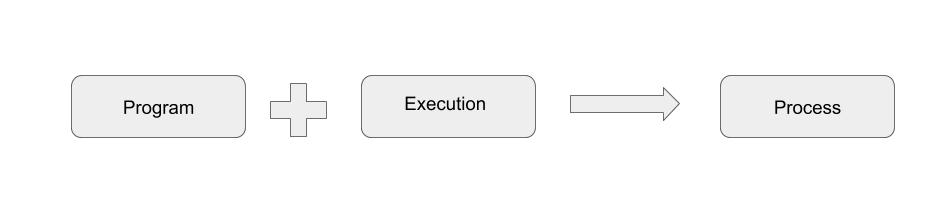

A process is created when a program is put into execution.

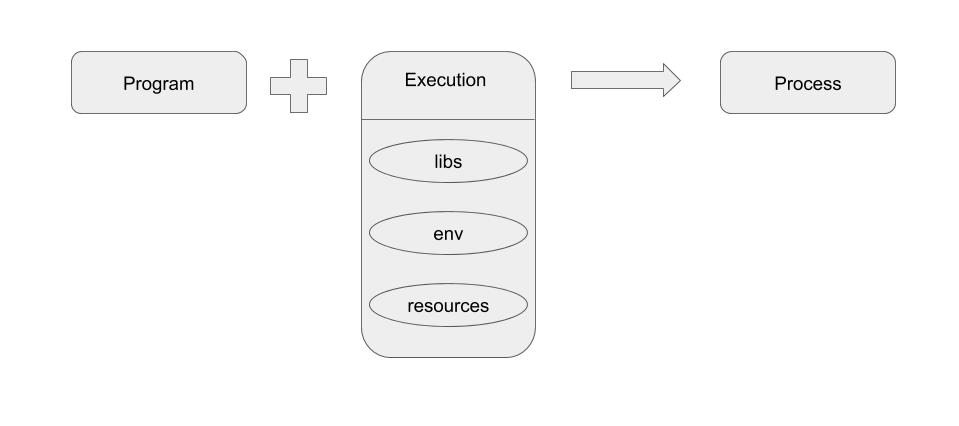

How can we execute a program? What are the requirements to execute a program?

A program needs libs, envs and resources to be able to put into execution and thereby create a process. For example, to execute a python script, we need python binary and some python modules, python environments and resources like cpu, memory, disk.

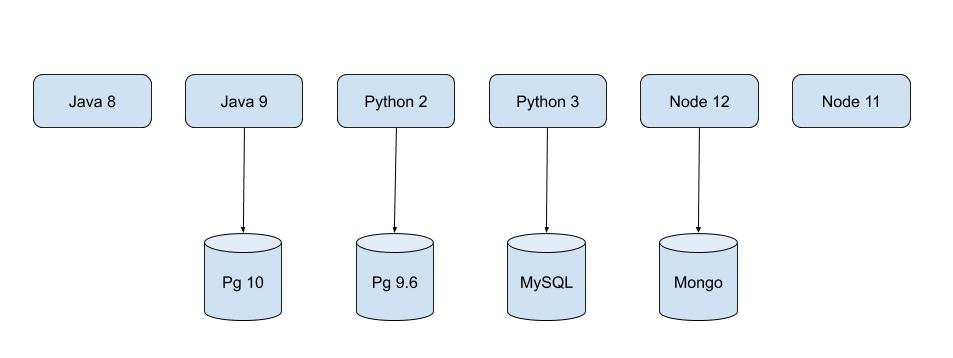

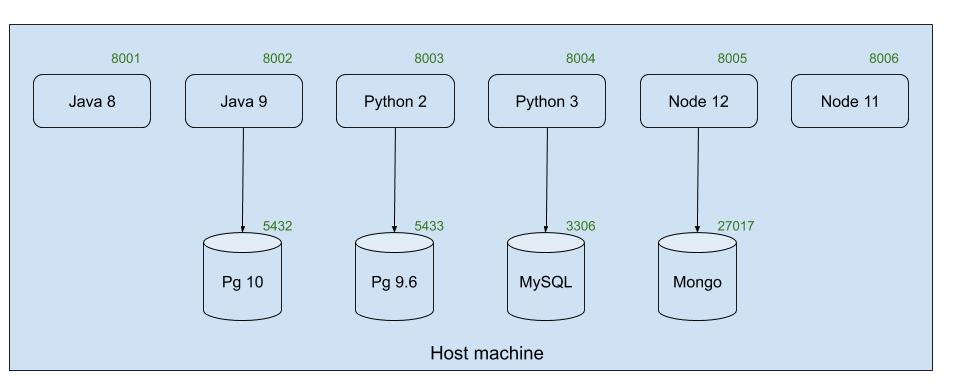

Let us consider a Web Application which consists of many microservices running on various languages and various versions. These microservices are nothing but a process at the backend.

Now that being said, imagine running these services in a physical machine… Thats not an easy task, ITS MERELY POSSIBLE

But Why? What is the challenge in running all these services of the same web application in a physical machine?

The problem is, suppose if the application has 2 Java services using different Java versions what will be the value for JAVA_HOME? There can’t be 2 JAVA_HOME set in a single physical machine.

If we have N services to be run in a machine, we have to assign the port to each service such that no port collision occurs. Think about running 2 versions of postgres, pg10 on 5432 port and pg9.6 on 5433 port. So all the services should be aware of the port it is running on.

To sum up the above mentioned challenge in a single word, there is NO ISOLATION.

Since there are different versions of libs and hence different envs are required, each and every service needs to be isolated from one another.

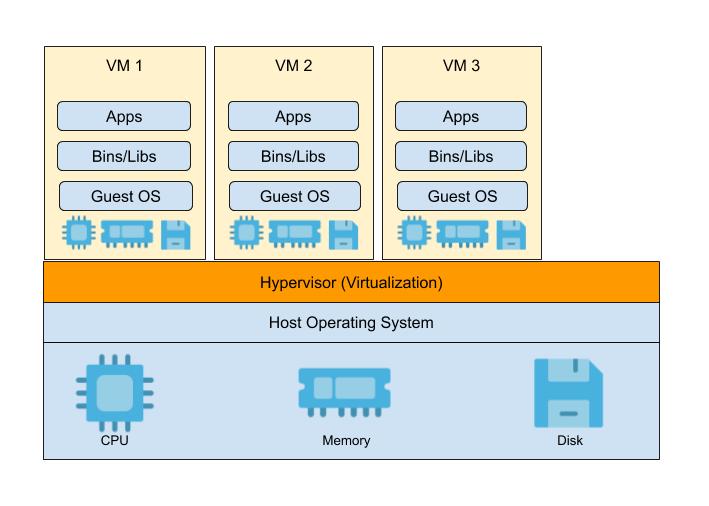

In order to isolate the processes, people started using Virtual Machines. Let’s see how Virtual Machines solve this problem.

Virtual machine is a separate guest OS created by an hypervisor running on a host machine. This separate guest OS, helps to achieve isolated libs, envs and resources.

But there are some challenges in using Virtual Machines in this case.

Think about running all the above services(processes) in a physical machine by creating required virtual machines(1 VM for 1 service).

You can evidently see the performance overhead in that physical machine which is running 10+ virtual machines. The reason being, the guest OS in each VM has its own memory management, network management and so on.

Not just that, proper resource utilization becomes a tough task while using Virtual Machines.

The main reason behind this overhead in Virtual machines approach is that the hypervisor virtualizes an hardware by creating guest OS for each VM.

All that we want is something which can isolate the libs, envs and resources without having to create separate OS. Why can’t we use the resource management of the Host OS itself instead of virtualizing the hardwares which results in overhead?

Yes, we have something called “CONTAINER” which is capable of doing the same for us.

A Container is nothing but an isolated process implemented by using some linux technologies like namespace and cgroup.

Now let us dive deep into containers, how they provide isolation to a process, what are namespaces and cgroup and how are they used.

Container is a group of process running on a host machine isolated by namespaces.

It provides OS level virtualization. Hence we can call it as “Lightweight VM”

We now have a basic understanding of what containers are. Next step would be how do we create it? I know many of us use docker to create containers using docker run command. But, is that the only option? No, there are few other tools like lxc, podman, etc. How the containers are created using these tools? What is the backend process?

To understand that, let us see how to create a container from scratch using linux technologies like namespace and cgroup.

Simple Container in Golang

Let’s create a simple go program which takes command as an argument and executes that command by creating a new process. Assume this go program as a docker. To execute a command in docker, we will use “docker run” command, similarly, here we use “go run container.go run”

package main

import (

"fmt"

"os"

"os/exec"

)

// go run container.go run <cmd> <args>

// docker run <cmd> <args>

func main() {

switch os.Args[1] {

case "run":

run()

default:

panic("invalid command!!")

}

}

func run() {

fmt.Printf("Running %v as PID %d \n", os.Args[2:], os.Getpid())

cmd := exec.Command(os.Args[2], os.Args[3:]...)

cmd.Stdin = os.Stdin

cmd.Stdout = os.Stdout

cmd.Stderr = os.Stderr

cmd.Run()

}

The above program executes the given arguments as a command. As you see below, “go run container run echo hello container” executes the command “echo hello container”. It executes the command by creating a new process which can be considered as a container.

Similarly let’s create a process using /bin/bash and assign a dedicated hostname for that container. But changing the hostname inside the container, changed the hostname of the host machine as well.

This happens because there is no isolation of hostname for this container. So, to create isolation of hostname, we can assign new UTS namespace for the container. In golang, we can do this by using the syscall package.

func run() {

fmt.Printf("Running %v as PID %d \n", os.Args[2:], os.Getpid())

cmd := exec.Command(os.Args[2], os.Args[3:]...)

cmd.Stdin = os.Stdin

cmd.Stdout = os.Stdout

cmd.Stderr = os.Stderr

cmd.SysProcAttr = &syscall.SysProcAttr{

Cloneflags: syscall.CLONE_NEWUTS,

}

cmd.Run()

}

Now, if you change the hostname of the container, it will not affect the hostname of the host machine because the container has its own UTS namespace.

But I want to assign the hostname automatically to the container from golang program using syscall syscall.Sethostname([]byte("container-demo")). But where can I place this line in the above program, the process is created on cmd.Run() and exited on the same line. Hence, let’s fork a child process and set hostname inside that.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"os"

"os/exec"

"syscall"

)

// go run container.go run <cmd> <args>

// docker run <cmd> <args>

func main() {

switch os.Args[1] {

case "run":

run()

case "child":

child()

default:

panic("invalid command!!")

}

}

func run() {

fmt.Printf("Running %v as PID %d \n", os.Args[2:], os.Getpid())

args := append([]string{"child"}, os.Args[2:]...)

cmd := exec.Command("/proc/self/exe", args...)

cmd.Stdin = os.Stdin

cmd.Stdout = os.Stdout

cmd.Stderr = os.Stderr

cmd.SysProcAttr = &syscall.SysProcAttr{

Cloneflags: syscall.CLONE_NEWUTS,

}

cmd.Run()

}

func child() {

fmt.Printf("Running %v as PID %d \n", os.Args[2:], os.Getpid())

syscall.Sethostname([]byte("container-demo"))

cmd := exec.Command(os.Args[2], os.Args[3:]...)

cmd.Stdin = os.Stdin

cmd.Stdout = os.Stdout

cmd.Stderr = os.Stderr

cmd.Run()

}

Another catch here is, the container is able to see all the processes running in the host machine.

A container should be able to see only the processes running in that container, which can be achieved by using PID namespace.

cmd.SysProcAttr = &syscall.SysProcAttr{

Cloneflags: syscall.CLONE_NEWUTS | syscall.CLONE_NEWPID,

}

Even then, the container is able to see the processes of the host machine. The reason is /proc; the container is using the same root filesystem as that of the host machine. Hence a different root file system is to be used for container and mount /proc into it.

/containerfs directory contains files of an operating system which has few binaries like python and core linux utilities. So mounting this directory as a root file system for container makes it self sufficient for linux utilities and not depend on host machine for binaries. It also provides separate environment for this container.

func child() {

fmt.Printf("Running %v as PID %d \n", os.Args[2:], os.Getpid())

syscall.Sethostname([]byte("container-demo"))

cmd := exec.Command(os.Args[2], os.Args[3:]...)

cmd.Stdin = os.Stdin

cmd.Stdout = os.Stdout

cmd.Stderr = os.Stderr

syscall.Chroot("/containerfs")

os.Chdir("/")

syscall.Mount("proc", "proc", "proc", 0, "")

cmd.Run()

}

Now we have achieved process id isolation using PID namespace. Similarly, we can provide isolation of network and users using network and user namespace.

Basically, the namespace is about what you can see in the container. It allows us to create restricted views of systems like the process tree, network interfaces, and mounts and users. These are the various namespaces that are available to provide isolation:

- UTS(Unix Time Sharing) namespace: hostname and domain name

- PID namespace: process number

- Mounts namespace: mount points

- IPC namespace: Inter Process Communication resources

- Network namespace: network resources

- User namespace: User and Group ID numbers

Now, let us see how resource management works in container. I have a python script hungry.py which consumes 10mb of memory for each 0.5 seconds. Running this python script using the container.go program, allows the container process to consume all of the memory available in the host machine.

To manage the resources like memory, cpu, disk blocks, we can use cgroups.

Every system has control groups in /sys/fs/cgroup/ and memory uses the default values from /sys/fs/cgroup/memory. You can see that the value in /sys/fs/cgroup/memory/memory.limit_in_bytes is very huge, allowing a process to consume memory as much as available in the host machine.

Here, in this go program, I am creating a control group prabhu and giving 100mb as maximum limit of memory and disabling the swap memory. And also assigning the process id of the container to the tasks of cgroup prabhu.

func child() {

fmt.Printf("Running %v as PID %d \n", os.Args[2:], os.Getpid())

syscall.Sethostname([]byte("container-demo"))

controlgroup()

cmd := exec.Command(os.Args[2], os.Args[3:]...)

cmd.Stdin = os.Stdin

cmd.Stdout = os.Stdout

cmd.Stderr = os.Stderr

syscall.Chroot("/containerfs")

os.Chdir("/")

syscall.Mount("proc", "proc", "proc", 0, "")

cmd.Run()

}

func controlgroup() {

cgPath := filepath.Join("/sys/fs/cgroup/memory", "prabhu")

os.Mkdir(cgPath, 0755)

ioutil.WriteFile(filepath.Join(cgPath, "memory.limit_in_bytes"), []byte("100000000"), 0700)

ioutil.WriteFile(filepath.Join(cgPath, "memory.swappiness"), []byte("0"), 0700)

ioutil.WriteFile(filepath.Join(cgPath, "tasks"), []byte(strconv.Itoa(os.Getpid())), 0700)

}

Since, cgroup prabhu assigned to the container process allows only 100mb of memory, the python process gets killed once it tries to exceed that memory limit.

By using cgroups, system administrators gain fine-grained control over allocating, prioritizing, denying, managing, and monitoring system resources. The hardware resources can be appropriately divided up among tasks and users, increasing overall efficiency. And hence we can use the cgroups for resource management in container ecosystem.

Here, I have created a simple container with isolation of hostname, mount(/proc) and process tree using corresponding namespaces and also did memory management for the container using cgroups.

Conclusion

Containers are just isolated groups of processes running on a single host and that isolation leverages several underlying technologies built into the Linux kernel like namespaces, cgroups and chroots.

This is how Docker is containerising the applications with many other features like storing and transferring the files in terms of docker images.

And Docker is not the only technology that helps to run containers. There are other options like Podman from RedHat, LXC Linux Containers and rkt from CoreOS(project closed now).

Inspired from Building a container from scratch in Go - Liz Rice (Microscaling Systems)